There was mounting anticipation as the queue moved through the foyer of the auditorium. We had come to hear one of our most celebrated illustrators and a recent children’s laureate, Chris Riddell – and the wait was very nearly over.

Oh, hang on. It was over. Even as we scrabbled for seats in the packed auditorium, the big screen at the front was filling with images. Political cartoons, book characters … an image of the speaker himself, then captioned, “I have a strange feeling of being watched.”

Oh, hang on. It was over. Even as we scrabbled for seats in the packed auditorium, the big screen at the front was filling with images. Political cartoons, book characters … an image of the speaker himself, then captioned, “I have a strange feeling of being watched.”

And so it continued for over an hour, as drawing after drawing flowed effortlessly from a soft pencil or stick of charcoal, giving substance to the stories. It was mesmeric. Like seeing live thinking on the page. Even in the Q&A, Chris thought through his fingers, his words glossing each emerging image. Perhaps this is what prompted one question about whether children should be taught this language of drawing, just as they are taught the language of writing. Chris’s wry reply: an ironic speculation about what would happen if drawing were subjected to the same methods of teaching and assessment as are now employed for conventional literacy.

Expounding his theme, “The age of the beautiful book”, Chris talked of the wonders of modern book production and of his negotiations with “The Department for Making Books Beautiful” (aka the production department). Matt coating, spot varnishing, foil embossing, sprayed edges and other technological tricks of the trade open up mouth-watering possibilities for an artefact that engages and delights all the senses. For reading, for children and adults alike, is so much more than making sense of the words and images on the page.

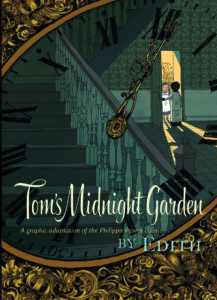

Books may be beautiful, but that doesn’t mean they have to be handled with kid gloves, at least as far as Chris is concerned. For him, a book is part of an ongoing conversation, and any space on the page an obvious invitation to get your pencil out. To the slight discomfort of those of us reprimanded for crayoning in books as children, he proceeded to draw all over a centre spread in a copy of Paul Stewart’s Returner’s Wealth – and then flipped over its pages to reveal his “illustrative annotations” proliferating through every chapter. But for Chris, this is just a natural response. “I’m drawing in books because I want to celebrate the book. Why would you not want to have a conversation with it?” he asks. And so word and image become part of a rich, intertextual dialogue. Chris’s own fiction, too, is part of that ongoing conversation, bringing in authors of his own childhood and earlier reading, including C S Lewis and Herman Melville.

As the conversation in the room unfolded, we were reminded of the sensory, visceral qualities of book-making – a process of creating where things have particularity and personality. It was truly a celebration of the delights of material book and the very primal activity of drawing with the hand. Surely one in the eye for all that digital nonsense!

Except, these drawings are constantly shared on social media. Sketches, drawings of odd quotations and the illustrative marginalia have, Chris has found, brought him closer to readers, allowed him to share enthusiasms, and even opened up opportunities for new projects. A recent convert (via an unfortunate incident involving a pair of jeans, his mobile phone and a washing machine) he quickly came to appreciate the power of the image on social media – as well as “the warm fuzzy glow produced by multiplying blue thumbs”. It seems like a marriage of some kind. Something old, something new, something borrowed, something blue.

Except, these drawings are constantly shared on social media. Sketches, drawings of odd quotations and the illustrative marginalia have, Chris has found, brought him closer to readers, allowed him to share enthusiasms, and even opened up opportunities for new projects. A recent convert (via an unfortunate incident involving a pair of jeans, his mobile phone and a washing machine) he quickly came to appreciate the power of the image on social media – as well as “the warm fuzzy glow produced by multiplying blue thumbs”. It seems like a marriage of some kind. Something old, something new, something borrowed, something blue.

New media inevitably cast old media in a new light. Certain aspects are thrown into relief. Benefits newly appreciated. So it would seem that if we are, as Chris believes “in the age of the beautiful book”, then technology has ushered it in – in all sorts of ways. And, as Chris demonstrated, there are so many possibilities for conversation between the old and the new, between the digital and the analogue.

But for all the exciting possibilities of machine and screen, paper and graphite always offer more. As Chris observed, if you watch people in a public space – one poring over a phone and one writing or drawing in a little notebook – you instinctively feel that there’s something much more interesting going on in the book.

After the talk, another queue: a line of hopefuls at the book-signing table. It was slow moving, but no one seemed to mind. Wine and conversation flowed all around, and one by one, happy readers left the table, each clutching their own beautiful book complete with its own personalised drawing.

Save